PRO TIPS

1) Don’t believe the naysayers: you can do a one-day round-trip visit from Yangon to the Golden Rock Pagoda (highly recommend hiring a car vs. going by bus)

2) Highly recommend taking the truck service up the mountain, it’s fun and safe (but not if you have motion sickness)

Kyaktiyo, or the Golden Rock Pagoda, is the most famous pilgrimage destination for Myanmar’s Buddhists. Together with the Mahamuni Buddha image in Mandalay and the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, it constitutes the “Grand Tour” that every Buddhist in the country hopes to accomplish at least once in his or her lifetime (with the caveat that women are not allowed the same access to the most-inner parts of either one of these). This was a big reason why I wanted to visit Kyaktiyo, having already visited the other two holy sites. I was also fascinated by the image of a giant rock, seemingly barely suspended by a thread over the void.

However, just prior to my trip, some friends who had been to Myanmar recently tried to discourage me, saying that it would take me two days, there was nothing else to see in the region, and at the end of the day, it was “just another pagoda” in a land full of them. Other tourists I met in Myanmar also supported the notion that I could not visit it as a day trip from Yangon. They had stayed at a hotel at the base of the mountain, thus making it a two day trip. And I just didn’t have an extra day to spend, as time was tight.

In the end though I decided to stick with my original plan, and attempt the day trip there. In a way I “cheated” because I left in the morning from Bago, which is already almost 2 hours away from Yangon. I also didn’t take the bus, but instead rented a private car (a taxi really) for the round-trip. My driver charged me 120,000 Kyat, but I then realized that I could have probably made the trip for 100,000, which is about the equivalent of $80 at the current exchange rate. Especially if you are traveling with more than one person, I think it’s not too bad. The added bonus was that I was able to recline my seat all the way and sleep for at least 2 hours of the 3.5 hours trip to the foot of the mountain.

As I wanted to catch the sunset over the Shwedagon Pagoda in Yangon, I knew I only had about three and a half hours in which to climb up the mountain, visit the pagoda grounds, and then climb down. I had heard that there were two options to go up the mountain, either in a semi-private jeep, or by taking the regular trucks, which are repurposed dump trucks fitted with metal benches. Since the Golden Rock Pagoda is the most important pilgrimage site in the country, thousands of people travel here from all over Myanmar every day. Trucks leave every five minutes or so to go up the mountain. My driver, U Soe, made the choice easy for me as he drove me straight to the truck stop terminal.

The energy level there is unreal. A throng of people is constantly rushing the empty trucks, not only approaching from the raised platform, but literally climbing on the trucks from all sides. It looks like an assault on the trucks. Understandably, I was a little perplexed and shy about the whole thing. Of course, I was the only foreigner in sight. But U Soe was gently encouraging me.

Go ahead, go ahead, no problem…

But I don’t have a ticket!

No problem. Go inside. Then buy ticket later.

Still not 100% comfortable with U Soe’s instructions, I nevertheless did as he told me and boarded the bus through the back, barely in time to squeeze into the last available seat. To my surprise, not only were there seat belts on the metal benches, but people were actually putting them on, which was a first in Myanmar. After we cleared the first control post (where I finally got to purchase a ticket for about 2,000 kyat), I understood why.

The ride up to Kyaktiyo is a real-world roller coaster! The road winds up the mountain at impossible angles, and while you generally go up, sometimes the road takes unexpected dips. And the whole thing at what seems an insane speed. Not for the faint of heart.

At times, the convoy of trucks inexplicably stops, seemingly in the middle of nowhere, but in reality in a spot where the road is large enough to allow another convoy of trucks coming from the other direction to descend the mountain. The drivers and the control posts use an ingenious walkie-talkie system (and other signals) to direct the two-way traffic on this one-way mountain road. I heard that when you purchase the private jeep ticket, you also get life insurance with it, but as far as the regular trucks, it seems that you are on your own!

Riding up and down the mountain was a big reason why I liked my trip to the Golden Rock so much. Especially on the way back, as I became emboldened and jumped off my seat to the back section of the truck, which is usually dedicated for larger pieces of luggage. With one leg strapped inside a hanging belt and holding on to the truck’s frame for dear life, I was able to “surf” by trying my best to keep my balance standing up while the truck was speeding down the narrow mountain road. But at every control post, I had to jump back in my seat, if not the driver would come around and scold me, even though he didn’t care when local kids did it!

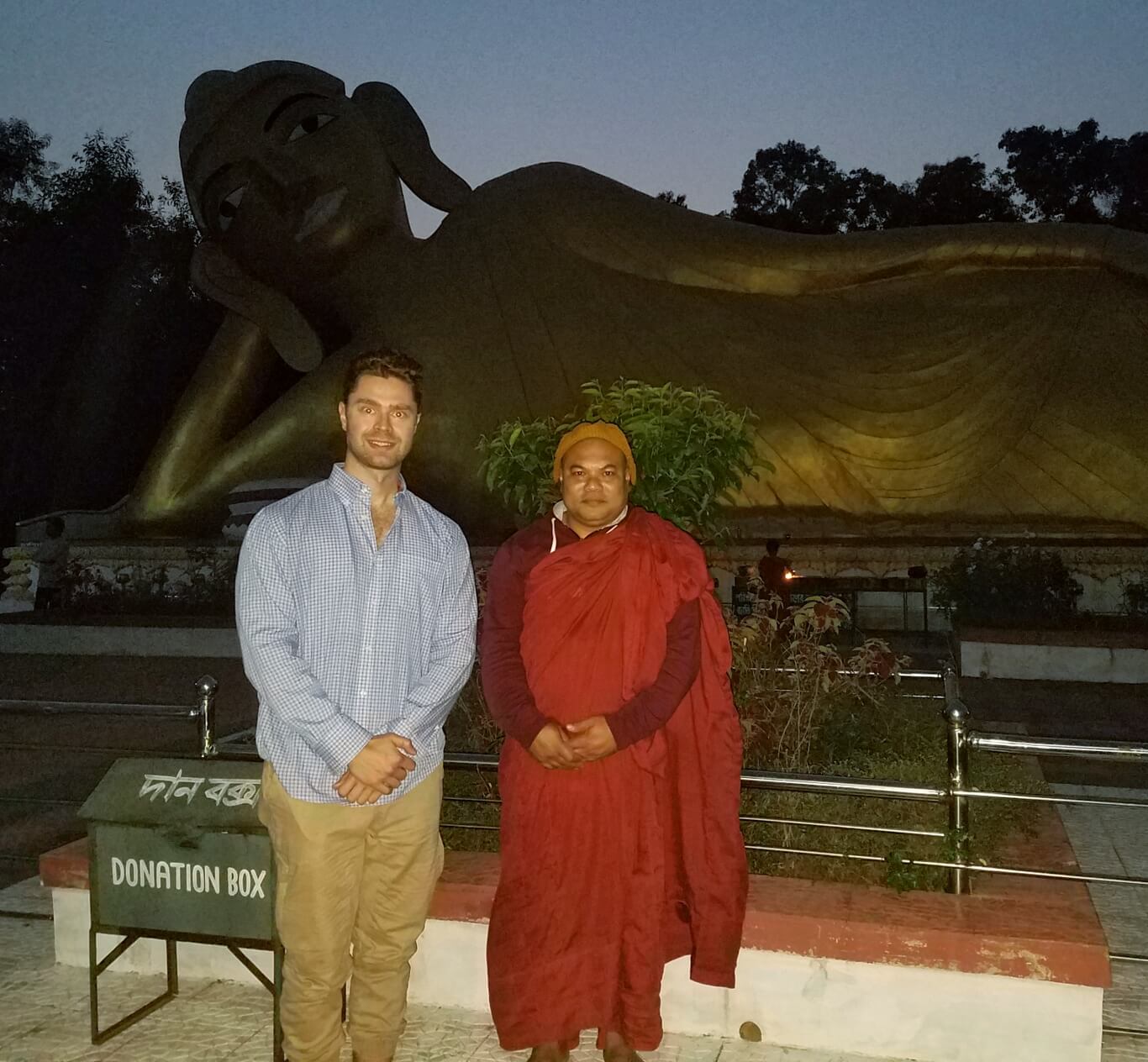

On my ride up the mountain, I was lucky to seat next to Sayarzaw Min, a Yangon private car driver who had just dropped off his customers at the jeep station, and was going to visit the pagoda himself until his customers decided to return to Yangon. We chatted a bit on the way up, but we really hit it off when got off at the mountain top and he gave me the best advice of the day: just walk the rest of the way, don’t use the porters. Had he not been there, I may have felt for it even though they were asking for the equivalent of $35 for what turned out to be less than a 10 minute walk to the entrance of the temple grounds itself.

So instead Sayarzaw and I just walked up the gentle slope, on a path choke-full of pilgrims, with innumerable vendors lining up both sides, selling anything from street food, to wooden beads, to kids toys, fruits and of course the ever-present betel nut rolled up in a leaf (kuon).

Before acceding to the topmost platform, from where you can actually see the Golden Rock, I had to pay the “foreigner fee” (around $10) and sign a foreigner “guest book”. Interestingly, I was only the third such visitor of the day, and the first American. And of course, we had to take our shoes off before entering the actual pagoda grounds, just like for any other pagoda in Myanmar.

Legend has it that the suspended Golden Rock is anchored to the ground by one hair strand of the Buddha. It is said that a Burmese hermit received the hair strand, and in turn donated it to a local king, who then built the pagoda to host it. Strangely enough, I have not been able to find anywhere the actual history of the pagoda, no information on when it was built, only that the road leading up to it was built in 1999. Before that, all pilgrims had to make the trek up the mountain by foot, taking about 3 hours. Even now, the more hardcore pilgrims do this trek, and then spend a night or two on top of the mountain, either in one of the guest houses or sleeping on the pagoda grounds themselves. And since the end of 2017, there is also a cable car that leads to the top, but what’s the fun in that?

Given the limited time I had, finding Sayarzaw was the best thing that happened to me that day. He was very familiar with the grounds, he knew exactly where to go to buy golden leaves (to put on the rock), he knew the good angles to shoot, and he also showed me parts of the temple complex I may not have thought of on my own. He really turned out to be clutch when I went to put the golden leaves on the rock itself. The Golden Rock is separated from the temple grounds, and to reach it one has to go through a metal detector and then a short draw bridge. The catch is that absolutely NO electronics are allowed past the metal detector, including cameras and cell phones. Had I been alone, I would have found myself in a real bind, with my backpack full of camera gear. But with Sayarzaw, I had no hesitation to leave ALL of my gear with him, including two pro cameras and 3 top-of-the-line lenses. Same as in Mandalay with my motorbike driver Sai Sai, I was able to develop a deep trust and understanding with him in a very short amount of time.

Once I returned from putting the gold leaves on the rock and saluting the Buddha, it was Sayarzaw’s turn. As a sign of our newfound friendship, I insisted on buying him some gold leaves too, and he in turn entrusted me with his cell phone and his personal bag, while he also went across the bridge to the Golden Rock.

While I waited for him, I noticed a fairly large covered area behind me—the ground of the temple gets really hot with the noon sun, and remember you can’t be wearing shoes!—where women and children sat chanting sutras and giving thanks to the Buddha. Just like at the Mahmuni temple in Mandalay or the Shwedagon in Yangon, women are strangely excluded from approaching the holiest site on temple grounds.

This is especially striking when considering that the Buddha was the first leader of a religious movement (or some would say a philosophical system) who openly welcomed women, and he even founded the order of Buddhist nuns during his lifetime, making it the oldest female monastic order in the world. Even more puzzling, the Buddhist path followed in Myanmar is called Theravada, which roughly translates to the path of the Ancients, meaning that practitioners only recognize the teachings contained in the Tripitika, the oldest Buddhist writings, as truly authentic, as opposed to Mahayana Buddhism, widespread in China, Tibet, Japan and Korea, which also includes more esoteric sutras. So, ironically, even though the Theravada Buddhists of Myanmar claim to be “closer” to the original teachings of the Buddha, they are less inclusive of women than many other, less “pure” forms of Buddhism! Apparently, this is based on tradition, and not necessarily Buddhist teachings, but it is still quite bewildering to see.

After the Golden Rock itself, Sayarzaw took me to the back of the temple where there is a large village/small town that spreads on the entire top of the mountain. Here can be found many guesthouses, as well as housing for the myriad of vendors who hawk their goods on the pagoda grounds. As I was losing track of time taking pictures, my friend reminded me that we needed to leave if I wanted to make it back to Yangon in time for the sunset. With regret, I followed him towards the bus terminal. But as soon as we got there, I cheered up again, anticipating another fun ride down the mountain.

Overall it was a bit of a difficult trip considering the driving time involved (close to 10 hours including the trucks up and down the mountain) versus the actual time spent at the pagoda (maybe an hour and a half at most), but well worth it. I didn’t get to eat all day, but the level of energy of the crowd at the Golden Rock was so high, that it spread to myself, and I didn’t even notice I was hungry. As usual, I was very careful to stay hydrated—I probably drank 8 litters of water that day—as the temperature reached into the low 100s F (37-39 Celsius), and by the time I realized I was hungry, I bought some grilled chicken skewers for around 300 kyat (25 cents!), and some locally prepared kuon (betel nut) to quench my hunger until we’d arrive back in Yangon.